The Ghost Mountain Boys Documentary Teaser (2024)

Ghost Mountain Expedition / PNG Tribal Foundation Teaser (2025)

In 1942, as the battle for the Pacific raged, a battalion of American soldiers spent 48 days crossing a deadly mountain range to drive the Japanese from Papua New Guinea. They trekked through some of the most geologically-disturbed terrain on earth: a chaotic jumble of sheer mountains and valleys, impenetrable jungle full of malarial mosquitoes, unknown tribes and poisonous snakes, weird icy forests of luminous fungi, and misty peaks where the earth itself seemed haunted. Chronicled in the book The Ghost Mountain Boys by author James Campbell, the journey of these soldiers and their subsequent battle at Buna—suffering a casualty rate of nearly 90%—is an astounding story of human courage and a meditation on the suffering experienced by men in conflict.

While researching this film, I discovered that my great uncle, Kenneth Warnock, served on the island then called New Guinea during WWII. He spent several years in fierce combat, and on his return, rarely spoke of his experiences there.

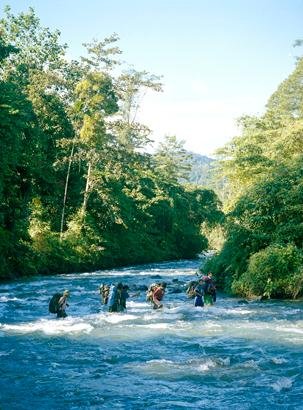

This fall, StoryHouse traveled to Papua New Guinea with author James Campbell, explorer Peter Gamgee and Gary Bustin of PNG Tribal Foundation to retrace the path taken by these men and visit a downed American C-47, The Flying Dutchman. Using interviews and footage from this trip, along with archival material, artistic recreations, satellite imagery and cutting-edge motion graphics, we’ll bring the story of these brave soldiers to life and create a powerful, moving film.

Artistic Vision

An impressive aspect of The Ghost Mountain Boys is its versatility of scope: the author’s willingness to appreciate tiny eddies of detail amidst the greater flows of history. Millions of Japanese soldiers swarm the Pacific, while a lonesome American surgeon pens a letter to his wife, listening to the Blue Danube Waltz. Perspectives of men from across the chain of command are juxtaposed. One minute we’re listening in as General Douglas MacArthur and Edwin F. Harding butt heads over the correct plan of attack for the 32nd Division, the next we are shivering in rainy mists over Ghost Mountain or up to our waists in swamp water with the enlisted men of Company G.

Our film will take a similar approach, constructing a spine out of likewise intimate moments in the experiences of men of the 32nd Division. These moments, selected for their historical and thematic content, will be ordered sequentially against the larger historical backdrop, and interwoven with a modern day trek along that same path. The result will be an immersive experience where the audience member feels connected to the story: not like they are attending a history lecture, but like they are living the story alongside the Ghost Mountain Boys in a real, detailed, visceral way.

Members of the team atop a pyramid in the Calakmul Archeological Site, Yucatan.

The Crew

I first met James Campbell while working on a video project for Panthera, a big cat conservation organization that researches and advocates for the world’s large cat species including lions, tigers, pumas and jaguars. In the summer of 2022 we followed renowned jaguar biologist Howard Quigley around the Yucatan as he assessed the impact of the forthcoming mega infrastructure project, the Maya Train, on the local jaguar habitat. Our director of photography, Taylor Turner, was also there, and it was a great chance for us all to get to know each other and work together.

James has been telling stories about earth’s wild places for a long time, first as a magazine writer and then as an author. His book, The Final Frontiersman, ended up being the inspiration for the television series The Last Alaskans. Like many of the Ghost Mountain Boys, James is a Wisconsin native and the story resonates for him personally. In 2006, he traveled to New Guinea to retrace the footsteps of the Ghost Mountain Boys across Papua New Guinea, and completed the arduous journey in spite of a debilitating knee injury. You can read about it here. During this trip, they shot over 40 hours of footage, which will also be a priceless asset for our project.

Accompanying us as well will be our Director of Photography, Taylor Turner. Taylor’s the perfect man for the job: he’s spent the last 10 years filming in Earth’s wildest places under the most extreme conditions. Head over to his website and watch his reel, you’ll be blown away! Taylor’s style fits perfectly with the imagery of Papua New Guinea: the deep jungles and peaks scarved in mist, the exotic animals and insects, the rich brown and green tones of mud and foliage, even the total darkness of night or the flickering orange of the evening’s cooking fire. It’s a wild, primal environment that hearkens back to the past of our ancestors, and should be feel like a threatening antagonist in and of itself.

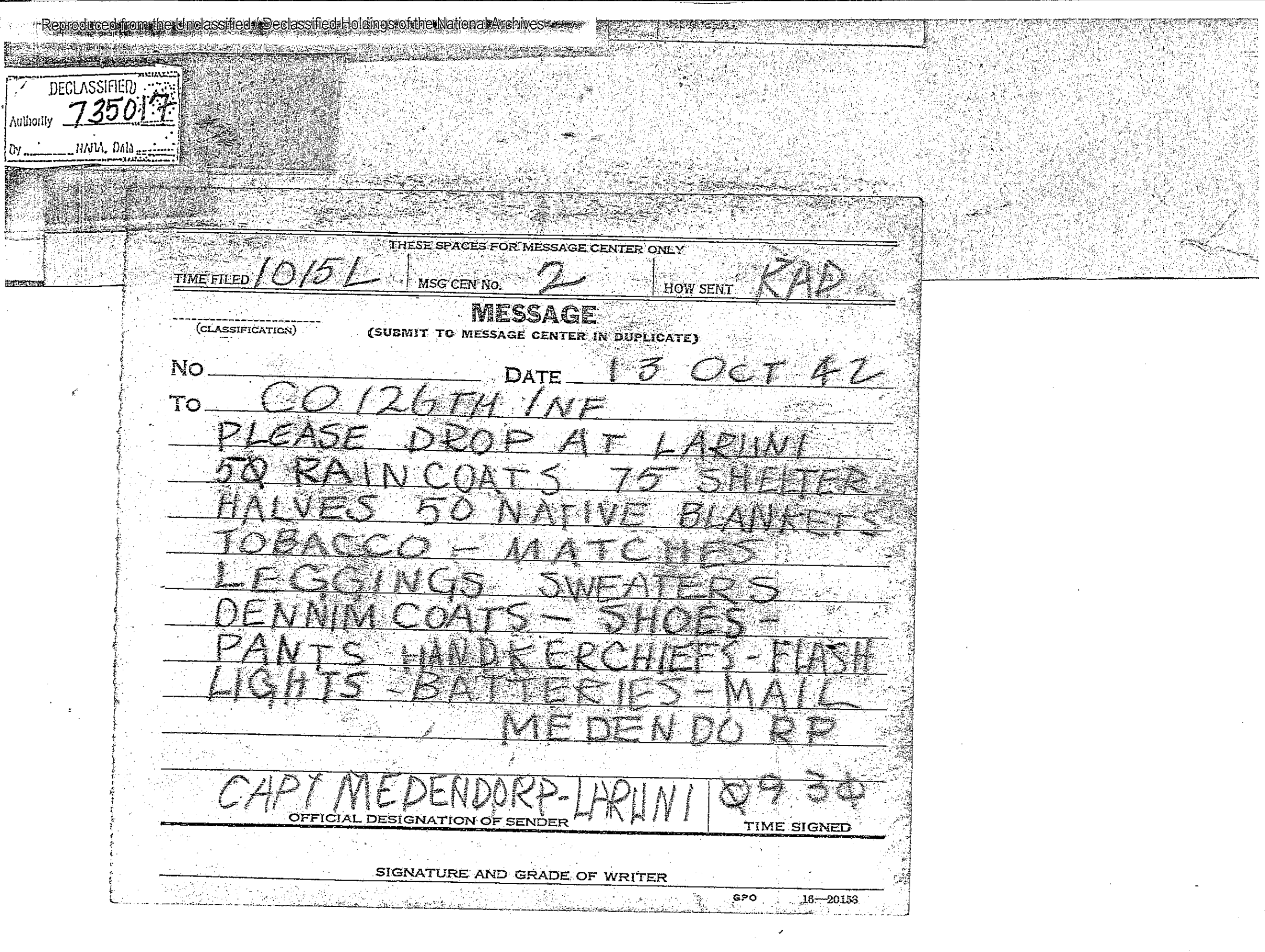

Archival

One exciting prospect is the rich archival material, much of which is in the public domain. Recent developments in technology have lowered the cost of image processing. We can now enlarge, adjust frame rates, interpolate frames, remove artifacts, dynamically-stretch, sharpen and color old archival footage at a very modest cost to our production budget.

Modern image processing tools help bring archival footage to life! This proof-of-concept video shows footage from New Guinea: one side has been scaled, interpolated, stabilized and colorized using Artemis and Stable Diffusion AI models.

I am also greatly interested in using archival material and documents in new, innovative ways. For example, we could imagine an opening sequence: in darkness, we hear the sound of a projector spinning up. The style of the music, title cards, and narration invokes training films of the time. A voice actor declares:

An illustration from Getting About In New Guinea advises the American serviceman to rely on the natives in an unfamiliar and hostile environment.

New Guinea is a primitive, hard country and a new world to men from overseas. You go there to fight a dangerous enemy, the Japanese. But they are not the only enemy. The country itself will fight you with all its forces — its mountains, swamps and forests, its heat and rain, its snakes, crocodiles, scorpions and lice, above all with its mosquitoes and its countless invisible army of disease germs…

These words are from an actual historical document, the Allied Geographical Section’s 1943 pamphlet Getting About In New Guinea. The audience member has become a draftee watching a training film, which through art, graphics and archival footage, advises them how to avoid the crocodiles, build lean-to’s, trap for bandicoots and generally get around in New Guinea. The sequence highlights in a lighthearted yet engaging way the extremity of the conditions these men would face, and just how difficult it would be to prepare soldiers for such conditions, and would make a perfect gateway into the film.

Such uses can be envisioned for various sequences. Historical sequences in general will be great creators of tension in the film, and sequences should be devoted to the Japanese national character and expansion, to Pearl Harbor, to the history of Papua New Guinea, to the impact of malaria and disease on the fighting in the Pacific, to Guadalcanal and the concurrent the fighting in Europe and Africa, and so on.

In this proof-of-concept video, Ghost Mountain looms over a possible route taken by soldiers of the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry. Using GPS data, Google Earth Studio, and a bit of After Effects wizardry, we can reconstruct the path taken by the original soldiers, all at a fraction of the cost of a big VFX studio.

Continuity

An oft-overlooked yet critical aspect of all film endeavors is known as continuity. While watching a film, we all subconsciously construct a a version of the film’s world inside our heads, with its own time and space. We’re searching for signposts, landmarks, things we can connect with to help us imagine ourselves inside that world and better understand it. If the filmmaker doesn’t give us enough information to do this, or suddenly violates our assumptions, we tend to get disoriented and lose interest in what we’re watching.

One thing I’ve noticed while working on videos about mountain expeditions is that it’s hard to help your audience understand where they are. There is often a strong sense of beginning (say, at base camp) and of completion (the summit), but middle of the film might get garbled with regards to time and space. Audiences can tune out, and the filmmaker fails to generate sufficient tension such that the final summit feels like a true achievement. It’s a difficult balance to maintain but one tool I’ve found helpful is quality maps and graphics, correlated very closely with what’s happening on screen. Check out the video above featuring of a technique I’ve been developing on our project about blind mountaineer Rafa Jaime. I’m very excited to apply these tools to the story of the Ghost Mountain Boys. Below, you can see another idea for helping people who are not familiar with the army understand the idea of Chain of Command.

Viewers must orient themselves in time and space, but also inside complex institutions such as the US Army. This is especially important for civilian viewers who are not familiar with Chain of Command. Graphics can help viewers understand characters and events with regards to this structure (proof-of-concept only, information not accurate). Also, these graphics are modular. For example, they might be combined in with the satellite maps above to show the location of various units along the trail or in the battlefield.

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence is currently revolutionizing content creation and providing incredibly powerful tools to filmmakers. As part of our effort to bring this forgotten history to life, we’ll be integrating cutting-edge AI tools to enhance the film’s visual and emotional impact. AI technology will be used to upscale, interpolate, and colorize archival footage, allowing audiences to experience historical moments with renewed clarity and immediacy. We will also animate select historical photographs to subtly reintroduce movement and presence, bridging the gap between past and present. Additionally, we plan to use AI-assisted voice synthesis, guided by historical research, to recreate unrecorded but documented statements — such as General Douglas MacArthur’s famous promise to the people of the Philippines, “I shall return”… Overall, the goal should be to use these tools in a way that is transparent, historically ethical, emotionally resonant, and revelatory for audience members.

Original Photo

Original Photo

AI Image-To-Video

AI Image-To-Video